Clustering concepts and correlation

Distances

Understanding distance metrics is critical for clustering and dimensionality reduction because these techniques heavily rely on measuring the similarity or dissimilarity between data points. Distance metrics define how “close” or “far” two points are in the feature space, and they play a crucial role in determining the grouping of similar points in clustering algorithms and the preservation of local and global structures in dimensionality reduction techniques.

Manhattan Distance

Manhattan distance, or L1 distance, measures the distance between two points by summing the absolute differences of their Cartesian coordinates. It is equivalent to the total number of moves required to go from one point to another if only axis-aligned moves (up, down, left, right) are allowed, mimicking a city grid.

Considerations

- Less influenced by outliers compared to Euclidean distance.

- Useful in high-dimensional spaces.

Euclidean Distance

Euclidean distance, also known as the L2 distance, is the most common metric used to measure the straight-line distance between two points in Euclidean space. It is the default distance measure in many analytical applications.

Considerations

- Measures the shortest path between points.

- Sensitive to outliers.

- Used in default settings for many algorithms like K-means clustering.

dist in R

# Load the iris dataset

data(iris)

iris_numeric <- iris[, 1:4] # Exclude the species column

# Euclidean distance

euclidean_distances <- dist(iris_numeric, method = "euclidean")

# Manhattan distance

manhattan_distances <- dist(iris_numeric, method = "manhattan")Clustering

Clustering is a technique used to group similar objects or data points together based on their characteristics or features. For example, clustering can be applied to gene expression data to identify groups of genes that behave similarly under different experimental conditions. These clusters might ultimately inform cell types or subtypes. There are several different clustering techniques, including hierarchical or K-means clustering. It is important to understand the limitations or assumptions of a clustering algorithm when applying it to your data.

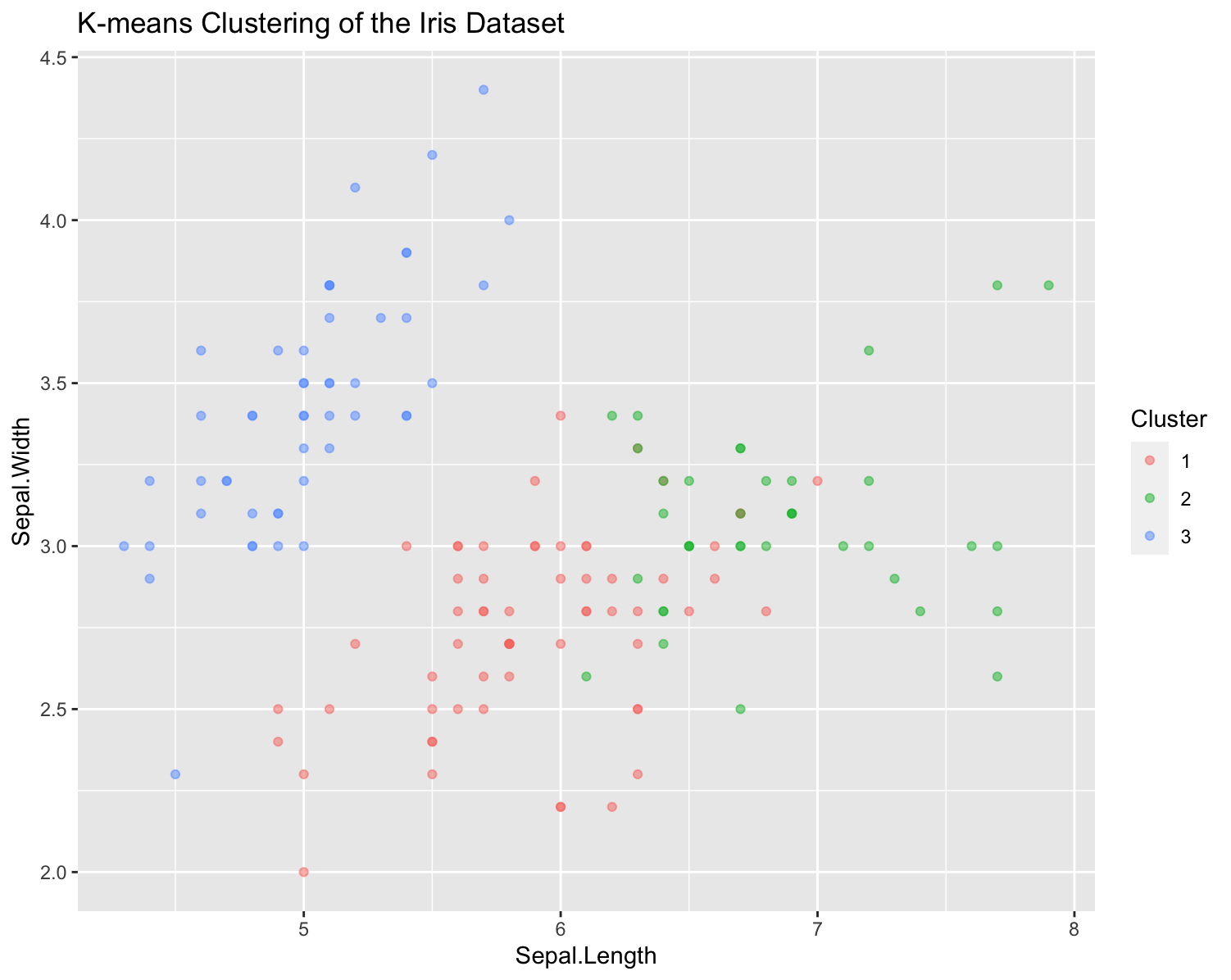

K-means clustering

K-means clustering is a popular unsupervised machine learning algorithm used for partitioning a dataset into a predetermined number of clusters. The goal of k-means clustering is to group data points into clusters such that data points within the same cluster are more similar to each other than to those in other clusters. The algorithm works iteratively to assign each data point to the nearest cluster centroid (center point of a cluster) and then update the centroid based on the mean of all data points assigned to that cluster. This process continues until the centroids no longer change significantly, or a specified number of iterations is reached.

K-means has some limitations, such as sensitivity to the initial random selection of centroids and the need to specify the number of clusters beforehand. Additionally, k-means may not perform well on datasets with non-spherical or irregularly shaped clusters.

Running on K-means on the iris data set:

# Load data

data(iris)

iris_data <- iris[, -5]

# Run k-means

set.seed(123)

kmeans_result <- kmeans(iris_data, centers = 3, nstart = 20)

# Results

print(kmeans_result)

table(Cluster = kmeans_result$cluster, Species = iris$Species)

# Visualization

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(iris, aes(Sepal.Length, Sepal.Width, color = factor(kmeans_result$cluster))) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.5) +

labs(color = 'Cluster') +

ggtitle("K-means Clustering of the Iris Dataset")

Heirarchical Clustering

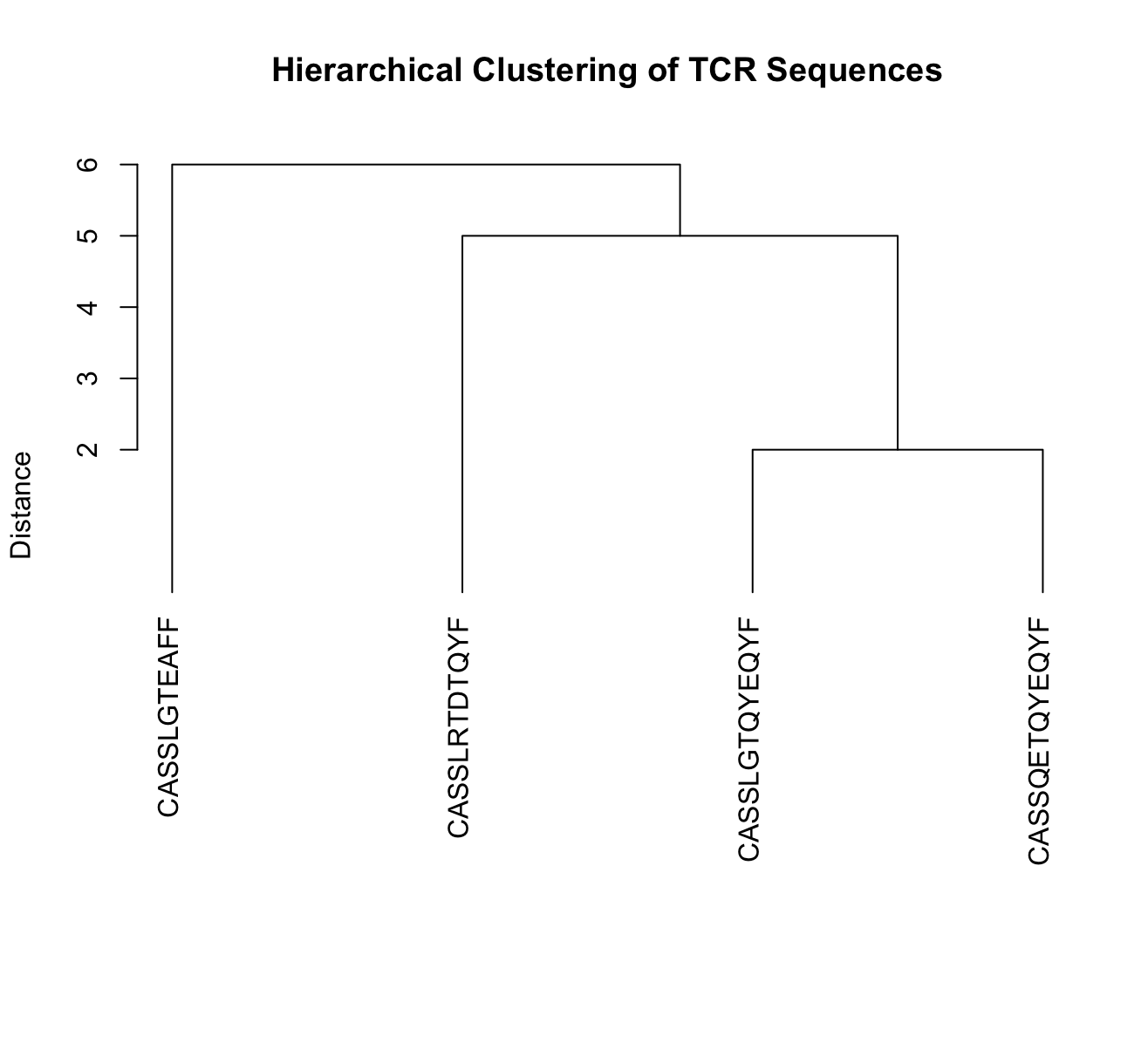

Hierarchical clustering is a method used in unsupervised learning to group similar data points into clusters based on their pairwise distances or similarities. The main idea behind hierarchical clustering is to build a hierarchy of clusters, where each data point starts in its own cluster and pairs of clusters are progressively merged until all points belong to a single cluster.

The result of hierarchical clustering is often visualized using a dendrogram, which is a tree-like diagram that illustrates the hierarchical structure of the clusters.

Lets use hclust on a set of TCR sequences, where the distance between each sequence is defined as the edit distance. We can plot a dendrogram highlighting sequence similarity.

# Install and load necessary packages

if (!requireNamespace("stringdist", quietly = TRUE)) {

install.packages("stringdist")

}

library(stringdist)

# Define TCR sequences

tcr_sequences <- c("CASSLGTQYEQYF", "CASSLGTEAFF", "CASSQETQYEQYF", "CASSLRTDTQYF")

names(tcr_sequences) <- tcr_sequences # Use sequences as labels

# Calculate pairwise string distances using the Levenshtein method

dist_matrix <- stringdistmatrix(tcr_sequences, tcr_sequences, method = "lv")

# Perform hierarchical clustering using the complete linkage method

hc <- hclust(as.dist(dist_matrix), method = "complete")

# Plot the dendrogram

plot(hc, main = "Hierarchical Clustering of TCR Sequences", sub = "", xlab = "", ylab = "Distance",

labels = names(tcr_sequences), hang = -1) # Ensure labels hang below the plot

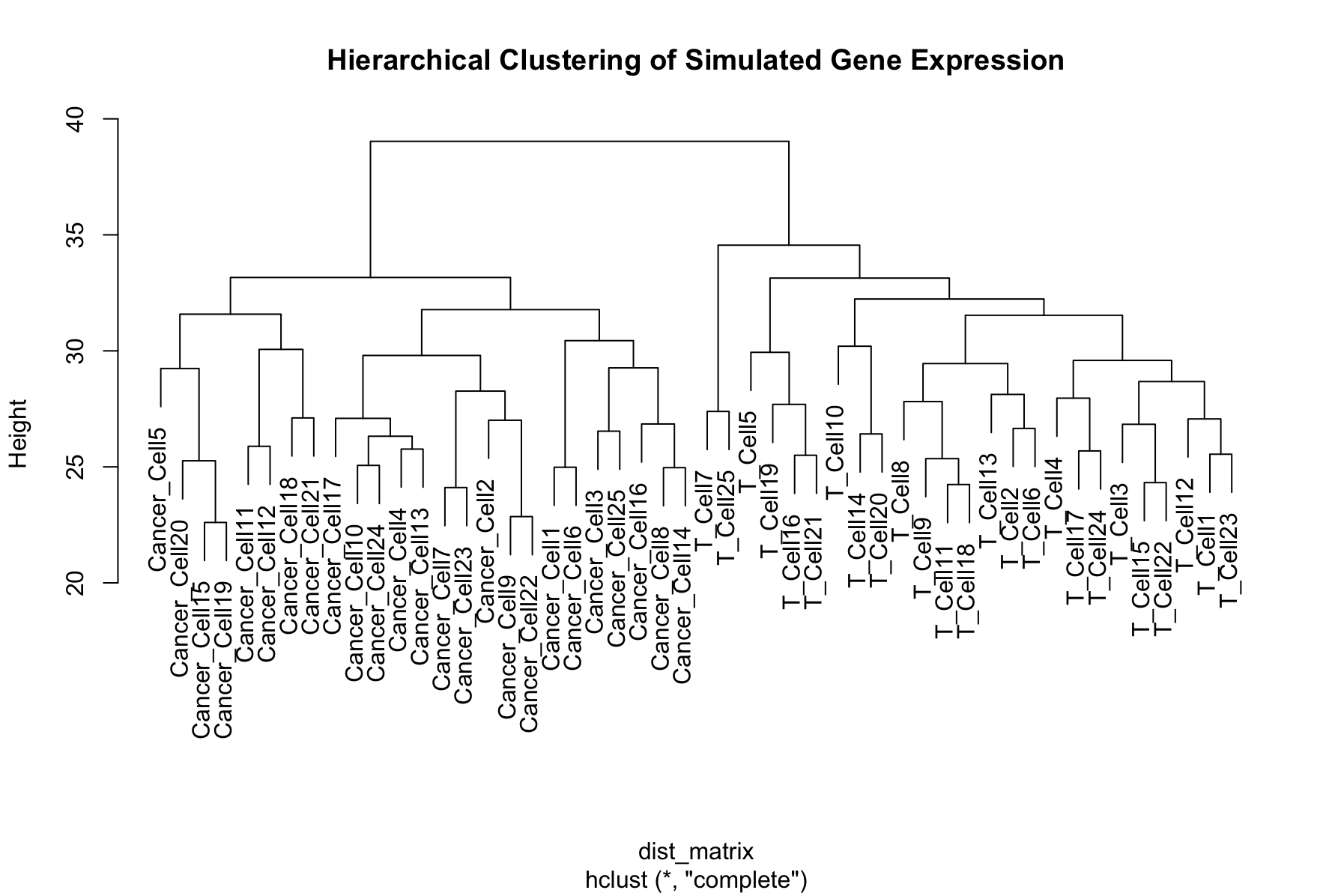

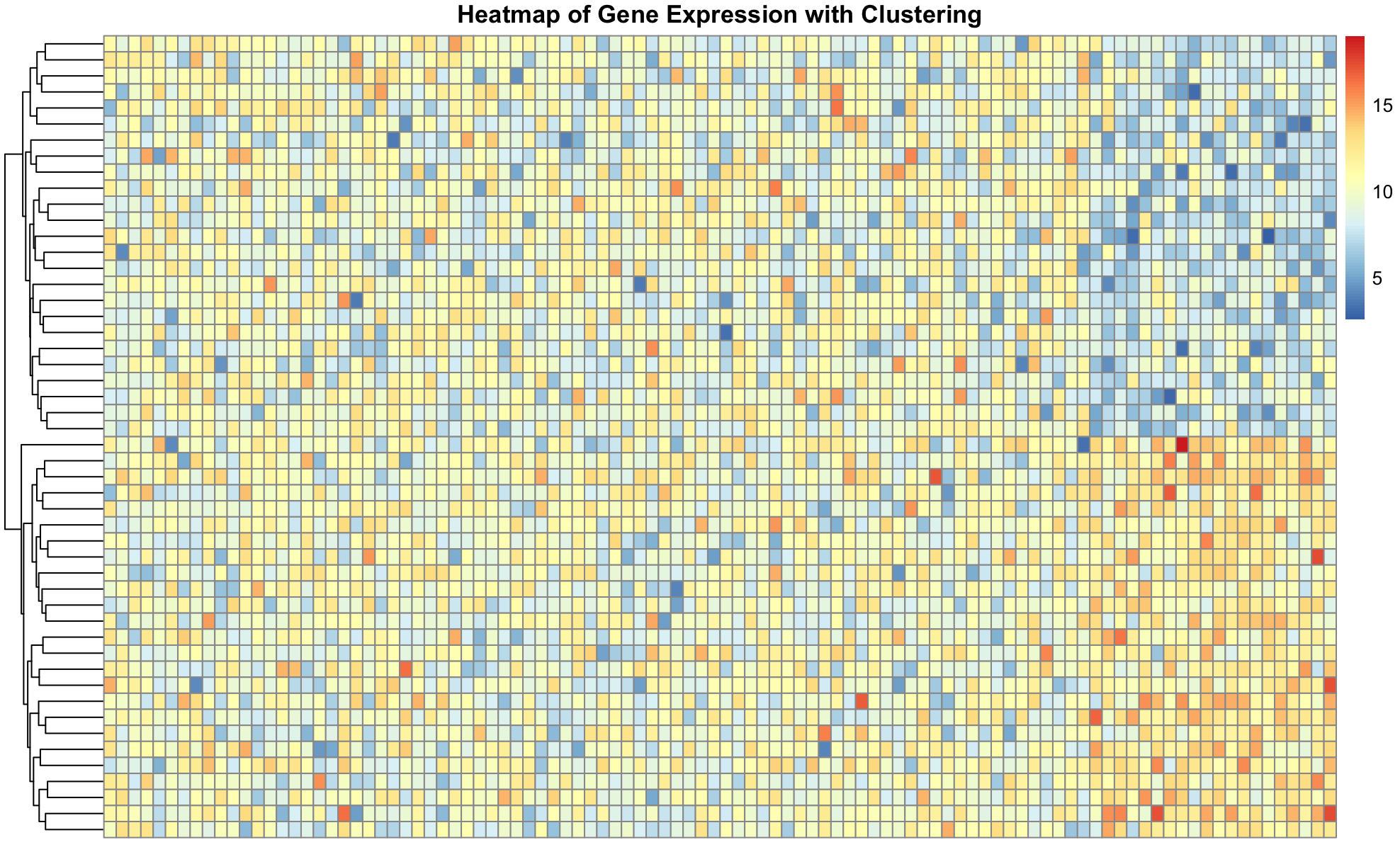

We can create a more complex simulated dataset of simulated single cell gene expression data. In this case, we have two cell types, and expect that the resulting dendrogram produced from the clustering should show clear differences between these cell types. Finally, we can plot the expression values in heatmap to visualize the difference between the genes across cells. The ordering of the rows is dictated by the dendrogram, drawing more similar cells closer together, allowing us to see the expression patterns that define each cell type.

# Install and load pheatmap if not already installed

if (!requireNamespace("pheatmap", quietly = TRUE)) {

install.packages("pheatmap")

}

library(pheatmap)

# Set seed for reproducibility

set.seed(42)

# Define parameters

num_genes <- 100

num_samples <- 50 # 25 T cells + 25 Cancer cells

# Simulate base gene expression

gene_expression <- matrix(rnorm(num_genes * num_samples, mean = 10, sd = 2),

nrow = num_genes, ncol = num_samples)

# Introduce differences in expression between the two groups

gene_expression[81:100, 1:25] <- gene_expression[81:100, 1:25] + 2 # T cells

gene_expression[81:100, 26:50] <- gene_expression[81:100, 26:50] - 2 # Cancer cells

# Label rows and columns

rownames(gene_expression) <- paste("Gene", 1:num_genes, sep = "")

colnames(gene_expression) <- c(paste("T_Cell", 1:25, sep = ""), paste("Cancer_Cell", 1:25, sep = ""))

# Transpose the gene expression matrix

transposed_gene_expression <- t(gene_expression)

# Creating a heatmap with clustering and annotation

pheatmap(transposed_gene_expression,

show_rownames = TRUE,

show_colnames = FALSE,

clustering_distance_rows = "euclidean",

cluster_rows = TRUE,

cluster_cols = FALSE,

main = "Heatmap of Gene Expression with Clustering")

Dimensionality Reduction

Dimension reduction is a crucial step in analyzing high-dimensional data, such as gene expression data, where the number of features (genes) is large compared to the number of samples (experimental conditions). Dimension reduction techniques aim to simplify the data while preserving its essential structure, simplifying hundreds or thousands of features into a two-dimensional space. For clustering cell types or samples, this approach enables the identification of which genes are the most different across groups or clusters.

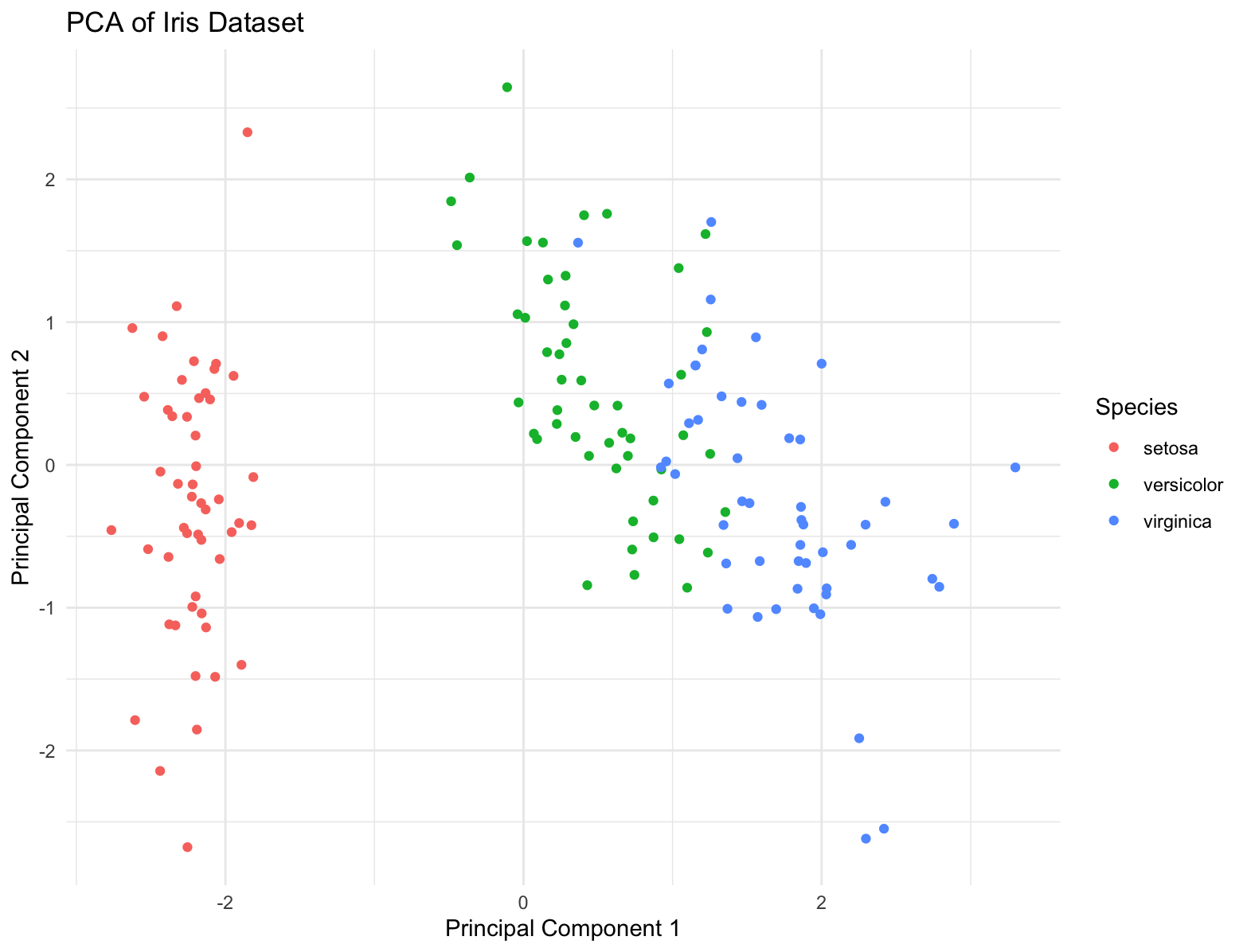

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a widely used dimension reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional representation by identifying the principal components that capture the maximum variance in the data. These principal components are orthogonal to each other and can be used to visualize the data in lower dimensions.

# Load necessary packages

library(ggplot2)

# Load data

data(iris)

iris_data <- iris[, 1:4]

# PCA

pca_results <- prcomp(iris_data, center = TRUE, scale. = TRUE)

print(summary(pca_results))

# Scatter plot of the first two PCs

pc_df <- data.frame(PC1 = pca_results$x[,1], PC2 = pca_results$x[,2], Species = iris$Species)

ggplot(pc_df, aes(x = PC1, y = PC2, color = Species)) +

geom_point() +

labs(title = "PCA of Iris Dataset",

x = "Principal Component 1",

y = "Principal Component 2") +

theme_minimal()

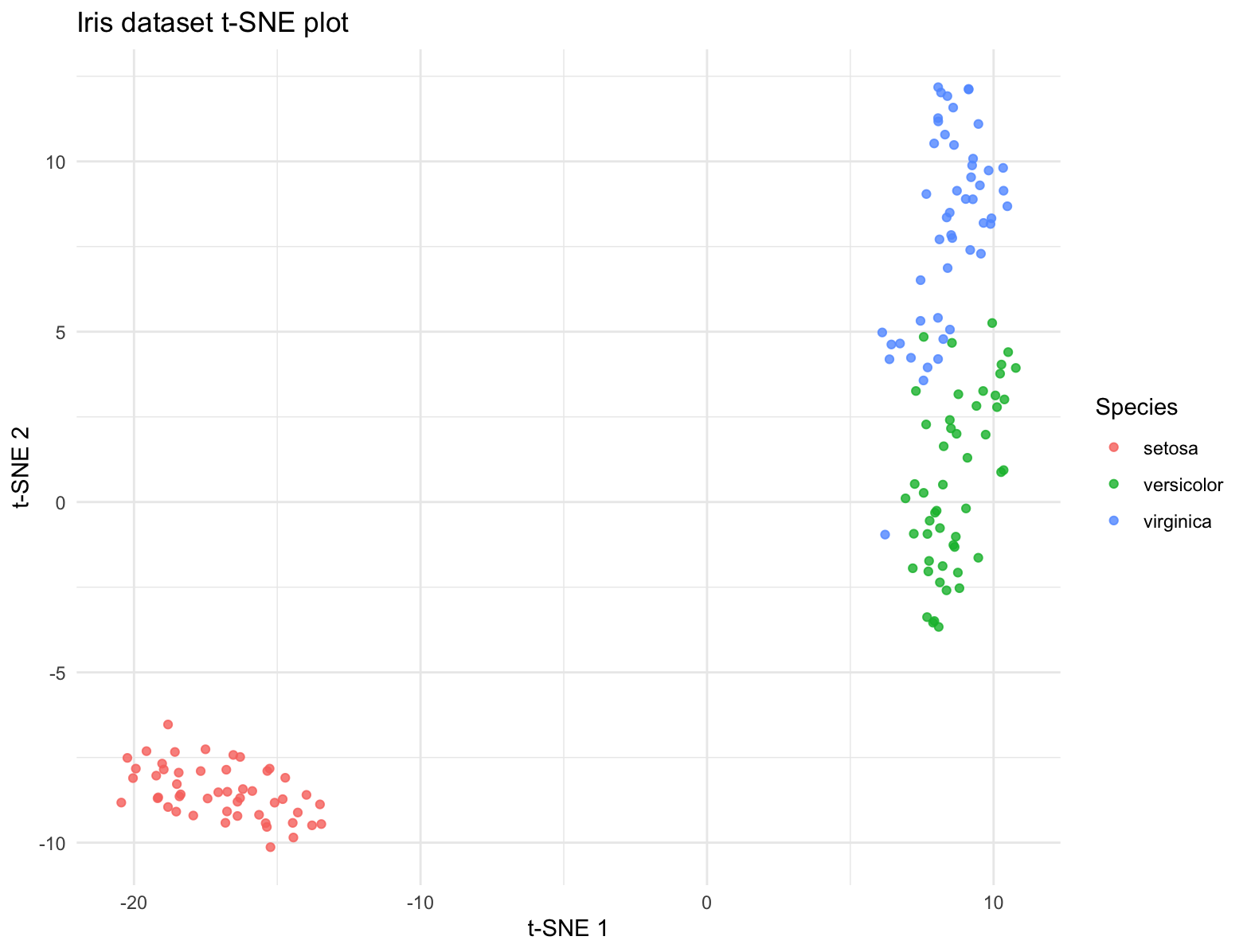

t-SNE

t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) is a dimensionality reduction technique commonly used in bioinformatics to visualize high-dimensional data, such as gene expression profiles or single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, in a lower-dimensional space. t-SNE aims to preserve local structure and clusterings in the data by modeling similarities between data points in the high-dimensional space and embedding them into a lower-dimensional space. In t-SNE, similarities between data points are represented by conditional probabilities that two points are similar given their high-dimensional representations. t-SNE iteratively adjusts the positions of data points in the lower-dimensional space to minimize the difference between the conditional probabilities of pairwise similarities in the high-dimensional and low-dimensional spaces.

# Load the Rtsne package

library(Rtsne)

unique_iris <- unique(iris[, 1:4])

# Run t-SNE on the deduplicated data

set.seed(42) # for reproducibility

tsne_results <- Rtsne(unique_iris, dims = 2, perplexity = 30, verbose = TRUE)

# Create a data frame for plotting (assuming you want to include species labels)

tsne_data <- data.frame(tsne_results$Y)

# Assuming you want to add back the species information

# This assumes that species information was not a factor in duplicates

# If species data was part of the duplication, handle accordingly

species_data <- iris[!duplicated(iris[, 1:4]), "Species"]

tsne_data$Species <- species_data

# Plot the results using ggplot2

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(tsne_data, aes(x = X1, y = X2, color = Species)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.8) +

labs(title = "Iris dataset t-SNE plot",

x = "t-SNE 1", y = "t-SNE 2") +

theme_minimal()

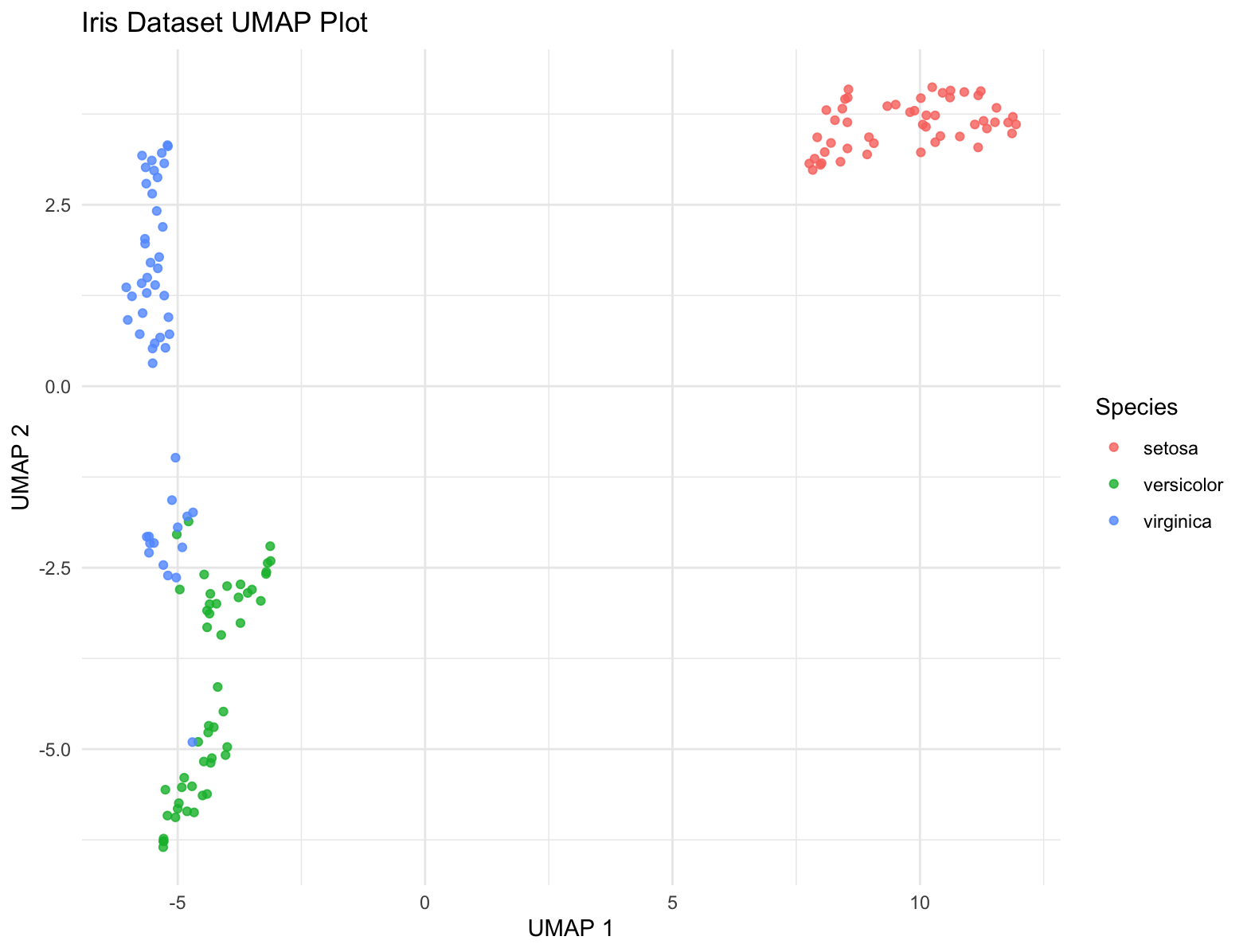

UMAP

UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) is a modern technique for dimensionality reduction that is particularly useful for visualizing clusters or groups in high-dimensional data. Similar to t-SNE, UMAP focuses on preserving the local structure of the data but also tries to retain more of the global structure compared to t-SNE. UMAP is based on manifold learning and operates under the assumption that the data is uniformly distributed on a locally connected Riemannian manifold.

# Install and load umap if not already installed

if (!requireNamespace("umap", quietly = TRUE)) {

install.packages("umap")

}

library(umap)

library(ggplot2)

# Load data

data(iris)

# Run UMAP

set.seed(42) # for reproducibility

umap_results <- umap(iris[, 1:4])

# Create a data frame for plotting

iris_umap <- data.frame(umap_results$layout)

iris_umap$Species = iris$Species

ggplot(iris_umap, aes(x = X1, y = X2, color = Species)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.8) +

labs(title = "Iris Dataset UMAP Plot",

x = "UMAP 1", y = "UMAP 2") +

theme_minimal()

Correlation

Correlation measures the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. In bioinformatics, correlation analysis is often used to explore relationships between gene expression levels across different samples or experimental conditions.

Spearman vs. Pearson Correlation

- Pearson Correlation: Measures the linear relationship between two variables. It assumes that the variables are normally distributed and have a linear relationship.

# Generate example data

set.seed(42)

x <- rnorm(100) # Generate 100 random numbers from a standard normal distribution

y <- x + rnorm(100, mean = 0, sd = 0.5) # Create y as a noisy version of x

# Calculate Pearson correlation coefficient

pearson_correlation <- cor(x, y, method = "pearson")

print(paste("Pearson correlation coefficient:", round(pearson_correlation, 2)))- Spearman Correlation: Measures the monotonic relationship between two variables. It does not assume linearity and is more robust to outliers and non-normal distributions.

# Generate example data

set.seed(42)

x <- rnorm(100) # Generate 100 random numbers from a standard normal distribution

y <- x + rnorm(100, mean = 0, sd = 0.5) # Create y as a noisy version of x

# Calculate Spearman correlation coefficient

spearman_correlation <- cor(x, y, method = "spearman")

print(paste("Spearman correlation coefficient:", round(spearman_correlation, 2)))geom_smooth

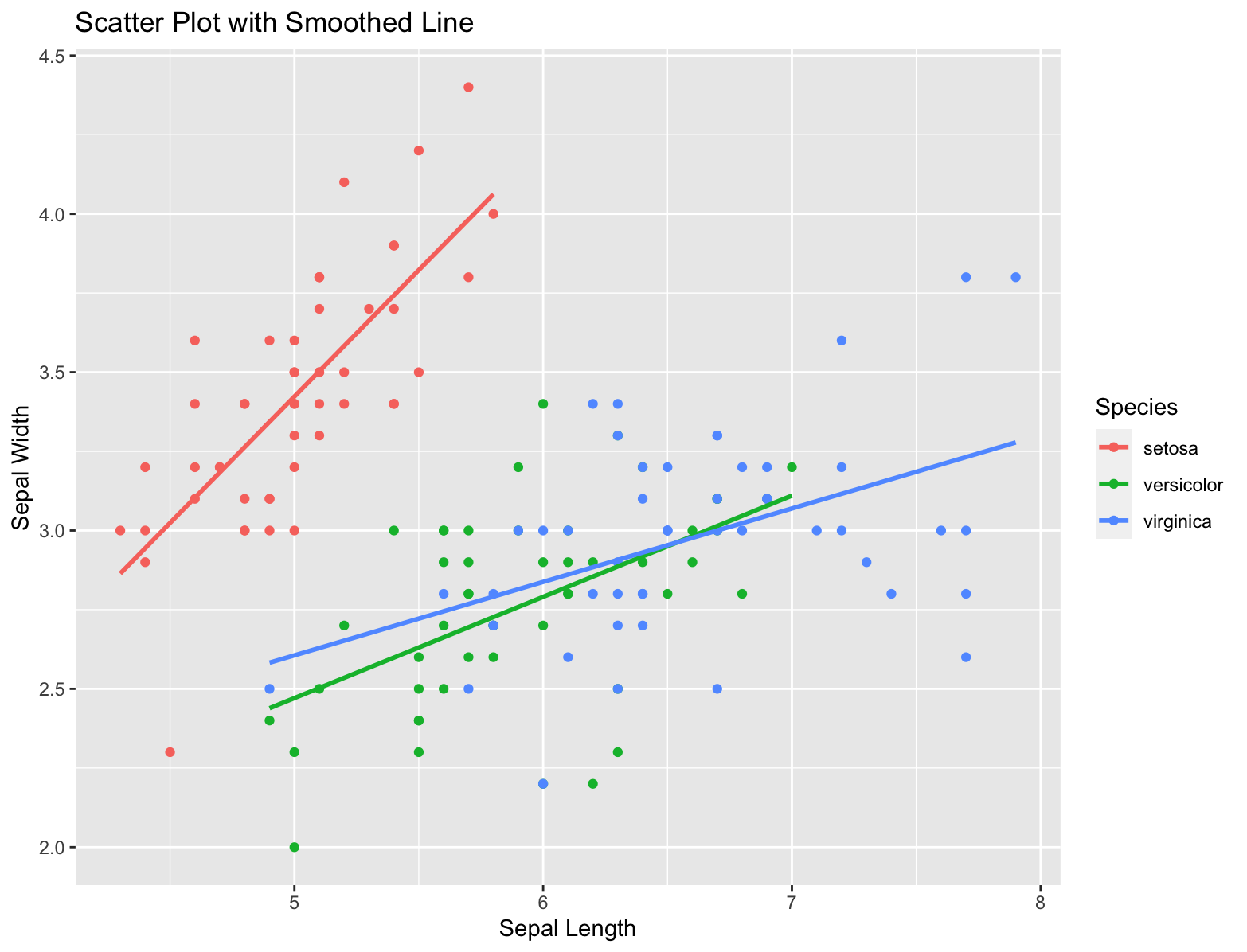

Simple example using iris.

library(ggplot2)

# Create a scatter plot with a smoothed line

ggplot(data = iris, aes(x = Sepal.Length, y = Sepal.Width, color = Species)) +

geom_point() + # Add scatter points

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) + # Add linear regression line

labs(title = "Scatter Plot with Smoothed Line", x = "Sepal Length", y = "Sepal Width")

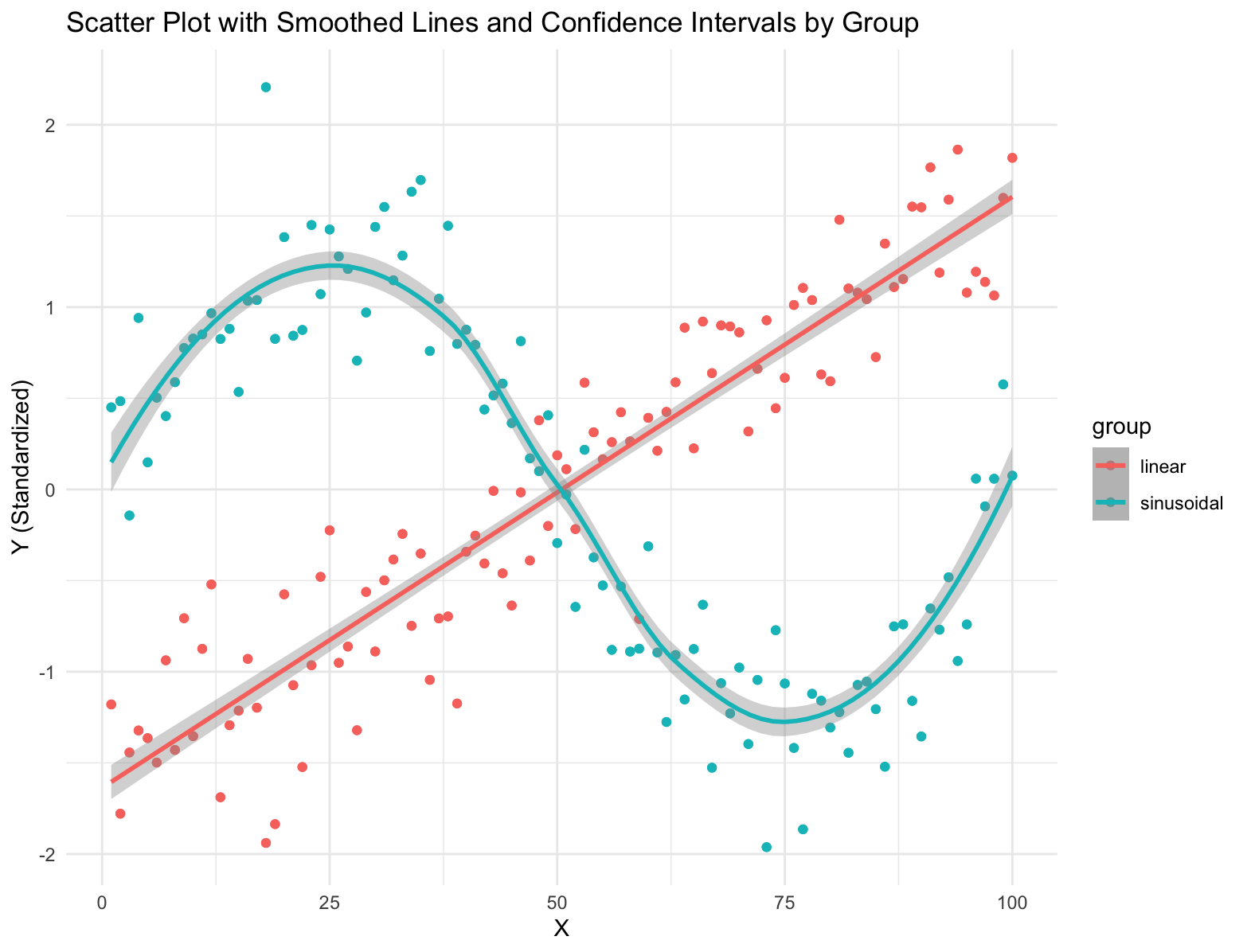

Simulate data points from two groups and use geom_smooth with a different model for each group.

# Load required libraries

library(ggplot2)

# Generate example data

set.seed(42)

n <- 100 # Number of data points per group

x <- 1:n # x values

group <- rep(c("linear", "sinusoidal"), each = n) # Group labels

y <- c(0.5 * x + rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 5), # Group 'linear' with a linear trend

2 * sin(seq(0, 2 * pi, length.out = n)) + rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 0.5)) # Group 'sinusoidal' with a sinusoidal trend

# Standardize y-values within each group

y <- ave(y, group, FUN = scale)

# Create a data frame

df <- data.frame(x = rep(x, 2), y = y, group = rep(group, 2))

# Plot the data with smoothed lines and confidence intervals for each group

ggplot(data = df, aes(x = x, y = y, color = group)) +

geom_point() + # Add scatter points

geom_smooth(data = subset(df, group == "linear"), method = "lm", se = TRUE) + # Add linear smoothed line with confidence intervals

geom_smooth(data = subset(df, group == "sinusoidal"), method = "loess", se = TRUE) + # Add sinusoidal smoothed line with confidence intervals

labs(title = "Scatter Plot with Smoothed Lines and Confidence Intervals by Group", x = "X", y = "Y (Standardized)") +

theme_minimal()

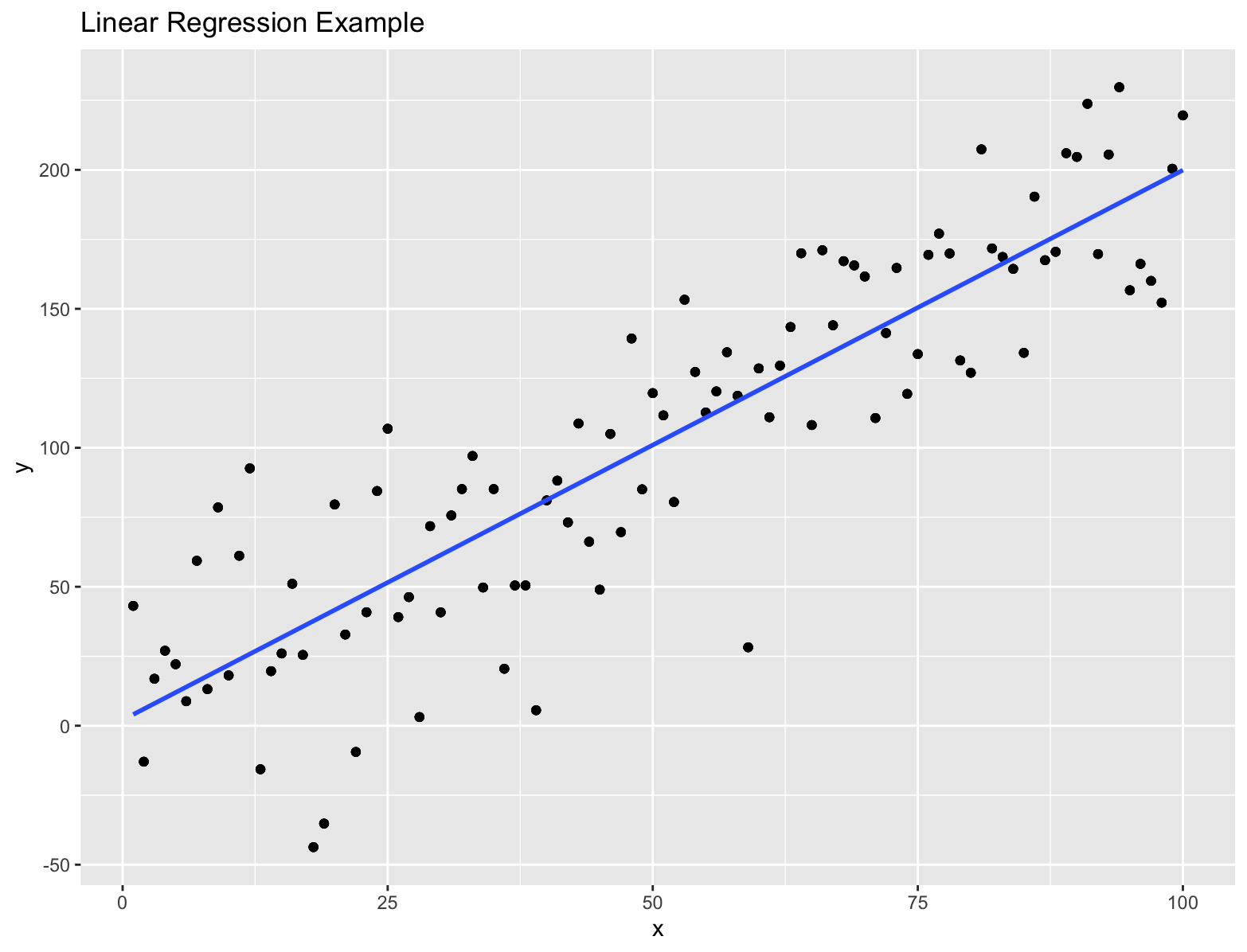

Linear Regression

Statistical model to estimate the linear relationship between a dependent variable and a set of independent variables. The goal is find the best fit line by fitting the observed data to a linear equation.

# Generate example data with more noise

set.seed(42)

df <- data.frame(x = 1:100, # Independent variable

y = 2 * df$x + rnorm(100, mean = 0, sd = 30)) # Dependent variable with more noise

model <- lm(y ~ x, data = df)

# Visualize the data and fitted line

ggplot(df, aes(x = x, y = y)) +

geom_point() + # Add scatter points

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE) + # Add fitted line

labs(title = "Linear Regression Example", x = "x", y = "y")

Example Code

# Load required libraries

library(ggpubr)

# Example dataframe

df <- data.frame(

Gene1 = c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5),

Gene2 = c(5, 4, 3, 2, 1),

Gene3 = c(2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

)

# Perform PCA

pca_result <- prcomp(df)

# Plot PCA

plot(pca_result$x[,1], pca_result$x[,2],

xlab = "PC1", ylab = "PC2",

main = "PCA Plot")

# Perform clustering

# Example clustering algorithm: k-means

kmeans_result <- kmeans(df, centers = 2)

# Plot clustering

plot(df, col = kmeans_result$cluster,

main = "Clustering Plot")

# Add correlation statistics to a plot

# Example plot

ggscatter(df, x = "Gene1", y = "Gene2",

add = "reg.line",

cor.coef = TRUE,

cor.method = "spearman",

cor.coeff.args = list(method = "spearman"))Additional Exercises

# Run PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP on the simulated gene expression data.

# CODE YOUR ANSWER HERE

# Run pheatmap again on the expression dataset, apply k_means clustering using 2, 10, 50 k's and view how clusters change

# Hint! type ?pheatmap to view function documentation in R

# CODE YOUR ANSWER HERE

# Save the pheatmap object to a variable, can you find which genes correspond to which clusters (use "$" to access object data)

# what cluster does Gene 5 correspond to

# CODE YOUR ANSWER HERE

Bonus Exercises: Heatmaps using ggplot2

library(ggdendro)

library(ggplot2)

library(tibble)

# Manually perform hierarchical clustering to generate heatmap using ggplot2

# Step 1. Perform distance functions

gene_distances <- dist(gene_expression, method = 'euclidean')

cell_distances <- dist(transposed_gene_expression, method = 'euclidean')

# Step 2. Perform hierarchical clustering

gene_clust <- hclust(gene_distances, method = 'complete')

cell_clust <- hclust(cell_distances, method = 'complete')

# Plot 1. Dendrograms

ggdendrogram(gene_clust, rotate = FALSE, size = 2)

ggdendrogram(cell_clust, rotate = FALSE, size = 2)

# Plot 2. Heatmap in ggplot2

gene_expression_df <- as.data.frame(gene_expression)

# Add column with gene name to data frame (originally rownames)

gene_expression_df <- rownames_to_column(gene_expression_df, "Gene")

# Prepare for plotting

for_plotting <- gene_expression_df %>%

gather(Cell, expression_value, -Gene)

# Code for plotting

ggplot(for_plotting, aes(x = Gene, y = Cell, fill = expression_value)) +

geom_tile() +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.text = element_blank(),

axis.ticks = element_blank())

# Reorder based upon clustering order

# Set Cell and Gene to factors (giving them a sorted order, based upon the hierarchical clustering)

# The order given by clustering is provided by the hclust_object$labels

reorder_plot <- for_plotting

reorder_plot$Gene <- factor(reorder_plot$Gene, levels = gene_clust$labels)

reorder_plot$Cell <- factor(reorder_plot$Cell, levels = cell_clust$labels)

ggplot(reorder_plot, aes(x = Gene, y = Cell, fill = expression_value)) +

geom_tile() +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.text = element_blank(),

axis.ticks = element_blank())

# How did the plot change?

# Make it pretty

ggplot(reorder_plot, aes(x = Gene, y = Cell, fill = expression_value)) +

geom_tile() +

scale_fill_viridis_c(option = 'rocket') +

coord_cartesian(expand = TRUE) + # removes blank space towards the edge

labs(fill = )

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.text = element_blank(),

axis.ticks = element_blank())

# How does the heatmap look different if you use other options for hierachical clustering?

# Hint: Try "ward.D2" or "centroid" for the method parameter.

# CODE YOUR ANSWER HERE

# Do you have a gene expression matrix of your own? Try creating a heatmap from your data!

# CODE YOUR ANSWER HERELecture Slides

The slides for this lecture are available here.